Companies:

Disney Interactive Sumo Digital

People: Charles Cecil

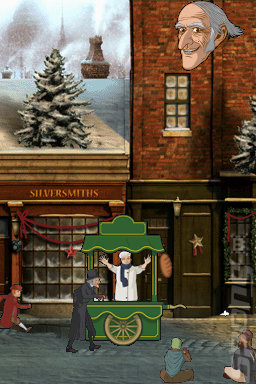

Games: Disney's A Christmas Carol (DS/DSi)

People: Charles Cecil

Games: Disney's A Christmas Carol (DS/DSi)

SPOnG: Speaking of the need to develop an adventure game, one of the main focal points of the genre is in the main character, that you take direct control of. The character is everything, some may say. You mentioned that you had to take a different tack with Scrooge as he's not your typical hero character. What would you say is the appeal in playing – or directly controlling – the life of a villainous character like Ebeneezer?

Charles Cecil: It's all on the humour. With A Christmas Carol, people love the story, and they love it because you have this mean old skinflint and you know that ultimately he will be redeemed. But there's also a lot of humour in the Dickens novel, and what I've tried to do is to convey that humour into the design of the game and to capture the joy of the story.

We all know what happens in A Christmas Carol, so story progression ended up being a reward, rather than integral to the game like in a traditional adventure title. For example, when Marley first appears Scrooge refuses to acknowledge that he exists. He puts it down to a bout of indigestion. What we took from that juncture in the book was some really nice gameplay ideas, to manipulate the scenario to convince Scrooge. So we came up with a system where you're the hand of fate controlling the environment.

So what you end up having to do is light the candle in his room to get enough light. But the candle blows out because the window is open. You close the window, but it'll open again unless you do something else. And only when you've got enough light and select the ghost whilst Scrooge is looking in that direction, does he have so much evidence that he can no longer deny its existence.

We went through the script looking for – and there are 14 different sections with loads of mini-games – examples of where the story had that element of humour. We took the essence of what the objective was in each example, and then we worked on how to turn that objective into gameplay.

SPOnG: How much do you think the adventure genre fits the world of A Christmas Carol? Do you think it's the best game style to suit that narrative?

Charles Cecil: Oh, absolutely! I can't think of any genre that it could possibly fit into.

SPOnG: Not a platformer, collecting baubles along the way, then?

Charles Cecil: (laughs) Well, absolutely not because if it was a platformer, then you would have to be controlling Scrooge. And if you're controlling Scrooge, the only thing you could really do would be against what a player is looking for in a game, generally speaking.

I don't even think a direct-role adventure would work, because then you have an unpleasant character doing things that you don't want. As a player you drive your character, and you've got to have an empathy with that character. Scrooge has to be one of the least empathetic characters you could possibly imagine. Therefore, the approach was spun on its head and we realised to drive indirectly rather than directly.

SPOnG: It's interesting that you chose an adventure game too, because the genre is having something of a resurgence lately after being neglected somewhat the last couple of years. Even in spite of this, you look at the gaming climate today and it's still predominantly first person shooters that dominate gamers' minds. Do you think there are still ways for the adventure game to evolve?

Charles Cecil: Very much so, and I think you've got a very interesting mix of games that are coming out today. I prefer to label it as an interesting mix, at any rate. I think that said, a good benchmark on which adventure games can be judged - and it's purely a gameplay angle – is that, when you get stuck, you know why.

What we've done in A Christmas Carol – as we did in Broken Sword – is to make it so that the player is never in a situation where they don't know how to progress. Hopefully people won't be playing the game, regularly scratching their heads as to what they're meant to be doing. They should know what to do, but the puzzle is in how to do it. And that's why mini-games work so well, because with a mini-game if you fail a couple of times that's alright, because next time you'll get it. It's building up the gameplay ramp.

What we had in the 1990s – the heyday of the adventure game – was that games were often set out specifically to frustrate the player. People would say they love adventure games because they think and think and think, they go to bed still thinking and in the morning they've got the answer. That's not a gameplay style that works anymore. So we've had to adapt radically.

But the emergence of the casual games market means that adventure games really are having a resurgence, because the reason that the genre was popular in the 90s is exactly the reason for its revival now. The new audience, a casual audience, is coming in, and they get bored of action 3D games or looking for hidden objects in the background fairly quickly. The adventure game is the ideal genre for that audience to move onto.

SPOnG: You touched upon the idea of storytelling in games just now. You can pretty much set up an adventure game these days in the form of an interactive book. Kids who aren't well versed in the story of A Christmas Carol would be more likely to 'read' the story in the form of a game where you direct Scrooge around and immerse yourself in his world. Do you think adventure games, to that end, is the best way to tell a story?

Charles Cecil: No doubt whatsoever. What would be great would be for kids to play the game and enjoy it, and then will want to read the book. When my children were young, they watched Baz Luhrmann's Romeo and Juliet, and in contrast Shakespeare's text was this impenetrable horror that was a chore to approach. But by producing Romeo and Juliet the way Baz Luhrmann did made the story very accessible – and the kids were then very keen to watch it and absorb the original Shakespeare story. We're talking quite young children too, about 7 or 8 years old at the time.

So if this game helps convey Dickens stories to a younger audience in the same way, then that would be a terrific side-effect to its goal of providing a great adventure experience.

SPOnG: Indeed, and even for adults today A Christmas Carol is very poignant, perhaps even more so than it has ever been with the whole economic climate that we're all experiencing. Would you say that the story of Ebeneezer Scrooge still has relevance in this day and age?

Charles Cecil: (Laughs) That is a great question! You are absolutely right, in that A Christmas Carol is ultimately about one man's greed and the fact the accumulation of wealth is more important that the relationships he has with the people around him. And that is so relevant to the banking crisis.

This hadn't actually struck me at all until you mentioned it just now, but I think you're absolutely right.

SPOnG: It's had me thinking for a while because these sorts of stories are timeless in its social relevance, and Dicken's tale was very relevant back when it was written and yet the reason it remains a classic is because such situations are easily repeated. And the morality the story contains could happen to anyone, right? I wouldn't even say Scrooge is a bad person, as he finds redemption at the end and was likely a good guy before he became set in his ways.

Charles Cecil: Well it's interesting isn't it, because the point at which Scrooge had his life-changing choice was with his girlfriend Belle. He had to choose whether to marry his love, and presumably spend some time not making any money; or to concentrate just on making money. He chose the latter and he lost his girlfriend, who went off and married someone else. That was the poignant moment in his life – obviously he then had the chance to redeem himself or face a life of utter misery.

I think the key question in the story, as in today's society, is how important should money be valued? Personally, I think that if you don't have enough money to survive then life can be miserable, but once you do have enough money to live by then having even more isn't of any great value. It's more important to have other values. So to me the story of A Christmas Carol is a very poignant one.

But clearly, you look at the bankers now, and they value money above anything else. That, to a political point, was what Margaret Thatcher created in the 1980s and was then continued by the Labour government. That is why we've gotten to where we are in society. But in the backlash will definitely come and money will generally be seen as less important than it has been in the last two decades.

… Ooh, that's a very political point, isn't it?

SPOnG: It is, we've somehow managed to turn A Christmas Carol into something very political indeed. Charles Cecil, thank you very much for your time.

Charles Cecil: It was a pleasure! Thank you.

Disney's A Christmas Carol is released on the Nintendo DS on the 6th November.

Charles Cecil: It's all on the humour. With A Christmas Carol, people love the story, and they love it because you have this mean old skinflint and you know that ultimately he will be redeemed. But there's also a lot of humour in the Dickens novel, and what I've tried to do is to convey that humour into the design of the game and to capture the joy of the story.

We all know what happens in A Christmas Carol, so story progression ended up being a reward, rather than integral to the game like in a traditional adventure title. For example, when Marley first appears Scrooge refuses to acknowledge that he exists. He puts it down to a bout of indigestion. What we took from that juncture in the book was some really nice gameplay ideas, to manipulate the scenario to convince Scrooge. So we came up with a system where you're the hand of fate controlling the environment.

So what you end up having to do is light the candle in his room to get enough light. But the candle blows out because the window is open. You close the window, but it'll open again unless you do something else. And only when you've got enough light and select the ghost whilst Scrooge is looking in that direction, does he have so much evidence that he can no longer deny its existence.

We went through the script looking for – and there are 14 different sections with loads of mini-games – examples of where the story had that element of humour. We took the essence of what the objective was in each example, and then we worked on how to turn that objective into gameplay.

SPOnG: How much do you think the adventure genre fits the world of A Christmas Carol? Do you think it's the best game style to suit that narrative?

Charles Cecil: Oh, absolutely! I can't think of any genre that it could possibly fit into.

SPOnG: Not a platformer, collecting baubles along the way, then?

Charles Cecil: (laughs) Well, absolutely not because if it was a platformer, then you would have to be controlling Scrooge. And if you're controlling Scrooge, the only thing you could really do would be against what a player is looking for in a game, generally speaking.

I don't even think a direct-role adventure would work, because then you have an unpleasant character doing things that you don't want. As a player you drive your character, and you've got to have an empathy with that character. Scrooge has to be one of the least empathetic characters you could possibly imagine. Therefore, the approach was spun on its head and we realised to drive indirectly rather than directly.

SPOnG: It's interesting that you chose an adventure game too, because the genre is having something of a resurgence lately after being neglected somewhat the last couple of years. Even in spite of this, you look at the gaming climate today and it's still predominantly first person shooters that dominate gamers' minds. Do you think there are still ways for the adventure game to evolve?

Charles Cecil: Very much so, and I think you've got a very interesting mix of games that are coming out today. I prefer to label it as an interesting mix, at any rate. I think that said, a good benchmark on which adventure games can be judged - and it's purely a gameplay angle – is that, when you get stuck, you know why.

What we've done in A Christmas Carol – as we did in Broken Sword – is to make it so that the player is never in a situation where they don't know how to progress. Hopefully people won't be playing the game, regularly scratching their heads as to what they're meant to be doing. They should know what to do, but the puzzle is in how to do it. And that's why mini-games work so well, because with a mini-game if you fail a couple of times that's alright, because next time you'll get it. It's building up the gameplay ramp.

What we had in the 1990s – the heyday of the adventure game – was that games were often set out specifically to frustrate the player. People would say they love adventure games because they think and think and think, they go to bed still thinking and in the morning they've got the answer. That's not a gameplay style that works anymore. So we've had to adapt radically.

But the emergence of the casual games market means that adventure games really are having a resurgence, because the reason that the genre was popular in the 90s is exactly the reason for its revival now. The new audience, a casual audience, is coming in, and they get bored of action 3D games or looking for hidden objects in the background fairly quickly. The adventure game is the ideal genre for that audience to move onto.

SPOnG: You touched upon the idea of storytelling in games just now. You can pretty much set up an adventure game these days in the form of an interactive book. Kids who aren't well versed in the story of A Christmas Carol would be more likely to 'read' the story in the form of a game where you direct Scrooge around and immerse yourself in his world. Do you think adventure games, to that end, is the best way to tell a story?

Charles Cecil: No doubt whatsoever. What would be great would be for kids to play the game and enjoy it, and then will want to read the book. When my children were young, they watched Baz Luhrmann's Romeo and Juliet, and in contrast Shakespeare's text was this impenetrable horror that was a chore to approach. But by producing Romeo and Juliet the way Baz Luhrmann did made the story very accessible – and the kids were then very keen to watch it and absorb the original Shakespeare story. We're talking quite young children too, about 7 or 8 years old at the time.

So if this game helps convey Dickens stories to a younger audience in the same way, then that would be a terrific side-effect to its goal of providing a great adventure experience.

SPOnG: Indeed, and even for adults today A Christmas Carol is very poignant, perhaps even more so than it has ever been with the whole economic climate that we're all experiencing. Would you say that the story of Ebeneezer Scrooge still has relevance in this day and age?

Charles Cecil: (Laughs) That is a great question! You are absolutely right, in that A Christmas Carol is ultimately about one man's greed and the fact the accumulation of wealth is more important that the relationships he has with the people around him. And that is so relevant to the banking crisis.

This hadn't actually struck me at all until you mentioned it just now, but I think you're absolutely right.

SPOnG: It's had me thinking for a while because these sorts of stories are timeless in its social relevance, and Dicken's tale was very relevant back when it was written and yet the reason it remains a classic is because such situations are easily repeated. And the morality the story contains could happen to anyone, right? I wouldn't even say Scrooge is a bad person, as he finds redemption at the end and was likely a good guy before he became set in his ways.

Charles Cecil: Well it's interesting isn't it, because the point at which Scrooge had his life-changing choice was with his girlfriend Belle. He had to choose whether to marry his love, and presumably spend some time not making any money; or to concentrate just on making money. He chose the latter and he lost his girlfriend, who went off and married someone else. That was the poignant moment in his life – obviously he then had the chance to redeem himself or face a life of utter misery.

I think the key question in the story, as in today's society, is how important should money be valued? Personally, I think that if you don't have enough money to survive then life can be miserable, but once you do have enough money to live by then having even more isn't of any great value. It's more important to have other values. So to me the story of A Christmas Carol is a very poignant one.

But clearly, you look at the bankers now, and they value money above anything else. That, to a political point, was what Margaret Thatcher created in the 1980s and was then continued by the Labour government. That is why we've gotten to where we are in society. But in the backlash will definitely come and money will generally be seen as less important than it has been in the last two decades.

… Ooh, that's a very political point, isn't it?

SPOnG: It is, we've somehow managed to turn A Christmas Carol into something very political indeed. Charles Cecil, thank you very much for your time.

Charles Cecil: It was a pleasure! Thank you.

Disney's A Christmas Carol is released on the Nintendo DS on the 6th November.

Companies:

Disney Interactive Sumo Digital

People: Charles Cecil

Games: Disney's A Christmas Carol (DS/DSi)

People: Charles Cecil

Games: Disney's A Christmas Carol (DS/DSi)